Veterans and The Brotherhood of War

Story by Nicole Trejo-Valli

Special thanks to former Pulse Editor and Army veteran Pete O'Cain for his assistance on this story.

You see them on campus and walk past them every day, but do you know the stories behind the uniforms? People enlist in the military for a variety of reasons, but one thing veterans at Central say they have in common: war can change a person.

Some view the military as a duty to their country, others as a family tradition, and still others as an educational benefit. Veterans make a sacrifice not everyone is willing to make, and each has their own reason for doing so. Pulse asked them to re ect on their motivations for enlisting, their experiences in the military and the challenges of transitioning back to civilian life.

ENLISTING

Although some veterans say the experience was bene cial, not all would necessarily do it again. For Ralf Greenwald, Navy veteran and associate professor of psychology at Central, military blood runs through his family—Greenwald’s dad served, his grandfather served, and his great-grandfather served, so it was a career he grew up with.

Still, he says he went into the military somewhat tentatively, thinking, “Let’s see how it goes, let me see if I can grow up a little bit more, save some of my own money for college, and then we’ll see down the road if maybe I like it [the military] and I’ll make a career out of it.”

He enlisted in the early ‘90s, and was a part of the rst Gulf War, Operation Desert Storm. He also served in the aftermath, Operation Southern Watches, and was in the Persian Gulf twice during Desert Storm for six-month deployments.

Darren Korthuis, Marine Corps Veteran and senior at Central, says the main reason he joined the war was because of Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF) when the U.S. invaded Iraq during the time he was in high school. He says he wanted to see it for himself and be a part of it.

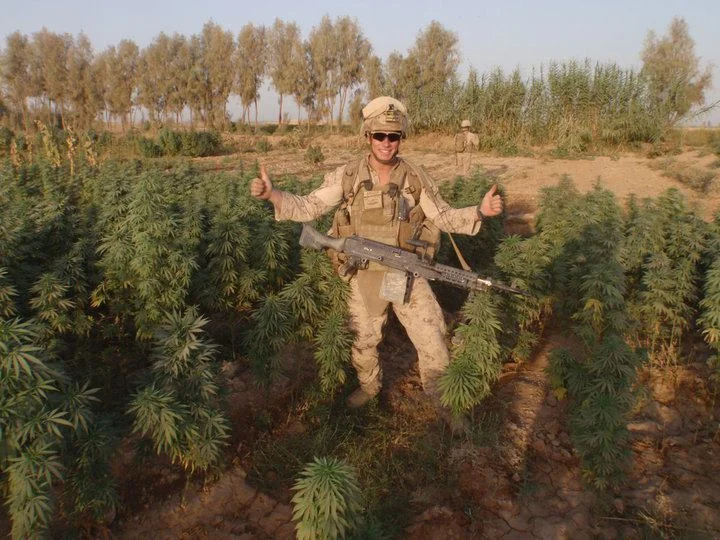

He was in the military for five years and went to Afghanistan in the summer of 2010 for seven months. Although he was in a kinetic area, which means there was a lot of action occurring, he says that was what he and his platoon wanted and their performance kept them there. If a war were to begin again, he says, “[If] I saw it as a ‘we needed to go back,’ then I would get back in.”

Ruben Cardenas, Army veteran and director of the Veteran Center at Central, had already finished his initial training and was back in class for two years before he was deployed in 2004.

He talks about how he was more relieved to be back home because he felt safe, as opposed to being on deployment where he always felt anxious of something to happen. “There are a lot of adrenaline rushes and a lot of lulls when you’re on deployment.”

But, he says, if he were to re-enlist now, things might be a bit different. “I feel pretty satisfied with being at home. It just depends on the conflict that we’re in at that moment.”

Justin Dennis, Army veteran and president of the Veteran’s Club at Central, never imagined himself serving. Prior to enlisting, he went to college but felt that he already known what they were teaching—so instead he started applying for jobs. And each interview he went to said the same thing, “[You have] all this training and knowledge but don’t have the experience.” But it wasn’t until his professor at the Wenatchee Valley College got the job network administration job he had wanted at the hospital that he decided to look for other options.

When he got home that night, an Army recruiter called him and said that he could give him the job experience if he wanted. This ultimately led Dennis to enlisting himself in the Army to get the experience he needed in the workforce.

“I enjoyed the time that I had and what I got out of it but I wouldn’t [re-enlist],” Dennis admits. “Not that I wouldn’t go back and do it again, but I wouldn’t do it again now.” He adds: “I wouldn’t say I regret going, I got a lot of good stuff out of my life in that period, but it’s not something I would want to do twice.”

ON THE BATTLEFIELD

College students today grew up in an era where con icts involving Americans in the Middle East have been going on almost their whole lives. But most of us don’t know what it’s actually like to be on the battlefield.

Dennis deployed in Dec. 2009 and spent four months in Kuwait, working 12- to 14-hour shifts doing computer networking. He was promoted and sent to Basra, Iraq at the beginning of June 2010. He describes Iraq as “a completely different world,” and “a night-and-day difference.”

Dennis remembers the night they arrived in Iraq and were attacked. “We got indirect re (IDF), which are mortars and rockets. When you get IDF you’re supposed to lay down and get at wherever you’re at because it sends debris up and away, so the safest place is on the ground.”

He recalls having to wait five to 10 minutes until he could move to a bunker or concrete building, and then wait an hour or two until the response team went out and found whoever was shooting. He says during that hour there is a mix of tension, boredom, and a morbid sense of humor—a lot of joking and half-hearted laughter goes on while waiting. And after the attack he explains it as a weird calm, where they just go back to their daily schedule.

It’s assumed that in war bad things happen, and those wounds can go both ways.

Korthuis says something he took away from his time in combat was that “there’s actually a deep hatred for Americans because of their lack of education and if they could cut our heads off and put it on YouTube, it would be their dream.”

“We worked with a lot of locals and saw a lot kids, and seeing their perspective of war was really interesting,” Korthuis says. “Seeing what war does to an area and why people in these foreign countries want to kill Americans is kind of weird. We kind of knew it going over there, but you don’t really see it or feel it till you’re there.”

Sometimes connections can be made with locals too, though. Greenwald describes a time he was working with some soldiers from the Saudi Arabian military and he was going through his mail. He had gotten a letter from his mom, who was in Germany, so it had German stamps on it. “ The Saudi soldier didn’t speak a lot of English but from what I gathered from him, he collected a lot of stamps,” Greenwald recalls. “He was super excited to see that I had these German stamps, and I was like ‘well, hey man, you can have these, I don’t need them, I don’t collect stamps.’”

“We just shared this moment, and it’s like at that moment you sort of realize, ‘man, this dude is no different than I am—he’s serving his country, he’s a young person like I am, he has his interests,’ and we just got along on that level. And then he shared some of his food with me and he was trying to tell me what it was and part of his culture.”

BROTHERHOOD

The other important connection people make in the military is with their peers. The US military has a unique ability to define brotherhood and sisterhood not only in words, but in actions.

“You go through all this stuff with a small group of people and even life or death situations and you just become close,” Cardenas explains. “When you spend so many hours, and days, and years with these people, and then you’re just completely removed, it’s like a piece that’s missing from you.”

Greenwald agrees. “I don’t think you had to have served in wartime necessarily to get that [brotherhood]—I think service in general, in the military, you’re going to form some bonds with people from all over the place.”

“Everyone has different opinions and different lives and backgrounds, and to get together with that group and work well, you really get to know that person, especially when you know, ‘hey, we could be in a situation someday where my life is going to depend on you and your actions.’ I think that just creates a special bond I feel is unique to veterans, and I really appreciate it in my life.”

War can bring out that comradery among people because of the situations they’re put through and their very real need to have each other’s back at any moment. And it can be those bonds that keep them going.

It was the close bond veterans have with one another, and his own experience with this, that Dennis says inspired him to want to bring back the Veterans Club at Central.

“It’s funny to see a Navy guy, an Army guy, and a Marines guy sit down and look at each other and it’s kind of this rivalry, then someone will say something, like ‘oh, did you go to Iraq? Oh yeah, I went to Iraq’ and then the whole group starts going and the shared experiences bring people together.”

Even as time passes, veterans still keep ties with those they served with. Some call and/or email back and forth, others join together with groups

COMING HOME

The transition back to civilian life can be difficult, and veterans say the mutual support is essential. ere are many factors at play, including how the conflicts are perceived at home, the severity of what they witnessed and had to do, or how an individual may cope after going through a stressful situation.

“I have fond memories of my time in the Navy for sure,” says Greenwald. “It wasn’t all fun and games, as anybody who served will tell you.”

But he and Korthuis both say that finding a support system was key when they transitioned back home. It’s “really difficult if you don’t have anybody you could sort of go to or that understands where you’ve been,” Greenwald says.

Greenwald had his family members who had also been in the military, as well as a close friend, his roommate, who had also served. They were there for him when he needed someone to talk to who understood what war was like.

Korthuis says his platoon from Afghanistan try to see each other every two years somewhere in the country. “Almost all the guys I went to Afghanistan with had similar stories—they had good transitions,” he says. “A lot of them used the GI Bill, the guys that were badly injured are getting taken care of by government programs, but everyone is doing pretty good.”

Cardenas also used the Post-9/11 GI Bill (Chapter 33) a form of the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944, to finish school once he got out of the Army. According to the US Department of Veteran Affairs website, the G.I. Bill provides educational assistance to service members, veterans and their dependents.

The G.I. Bill is considered one of the most significant pieces of legislation by the federal government in terms of its impact on the country socially, economically and politically—It enriched the U.S. by producing 450,000 engineers, 240,000 accoun- tants, 238,000 teachers, 91,000 scientists, 67,000 doctors and 22,000 dentists.

OFF THE BATTLEFIELD: POST-TRAUMATIC DISORDER

When the Vietnam War ended and soldiers came home, it was a much different environment than it is now. During that time, soldiers were looked down upon and post-traumatic stress disorder hadn’t even been recognized—It was just called shellshock.

That’s what happened to Rick Francis, a Vietnam veteran, who lives in Olympia with no relation to Central. When he returned he says he wasn’t able to readjust to civilian life and ended up getting in trouble.

He recalls a specific event when he was driving to his mountain home and momentarily mistook a spider web reflected in the mountain dew for a tripwire on the battle field. He slammed on the brakes and almost slid o the road. “I’m not in Vietnam anymore, this is ridiculous,” he recalls thinking. “But that reflex is, ‘No, you can’t drive through that.’ You’re second-guessing yourself.”

He says he realizes now he was showing signs of PTSD.

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a mental health problem that people can develop after experiencing or witnessing a life-threatening event, according to the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) website. PTSD can develop due to a range of reasons: a natural disaster, a car accident, sexual assault or combat, and the website clarifies that PTSD is not a sign of weakness and it’s out of the person’s control.

In April 2016, the O ce of Public and Inter- governmental A airs released the nation’s largest analysis of veteran suicide by the VA. e report covered more than 55 million veterans, from 1979 to 2014, from every state in the nation.

The analysis recorded an average of 20 veterans a day dying from suicide in 2014, down from 22 per day in a 2012 report. Approximately 65 percent of all veterans who died from suicide in 2014 were either 50 years of age or older, the report noted.

Between 2001 and 2014, the report continues and states that suicide among U.S. veterans who use VA services has increased by 8.8 percent, while among those who didn’t use the services, suicide increased by 38.6 percent.

The rates are vastly different for genders: an increase of 11 percent for males versus 4.6 percent for females who use VA services, and for those who do not use VA services, the rates increased for males by 35% and for females by an alarming 98%.

It should be noted, however, that the data provided in the April 2016 analysis showed a 24% increase in suicide rates in the general population between 1979 to 2014 for both males and females.

Efforts have increased to provide suicide prevention measures through the VA to create outreach groups among veterans, much like Central’s Veterans Club.

Justin Dennis, Iraq Army Veteran and president of the Veterans Club, started the club with his wife in spring quarter of 2016. Dennis knew he had a strong friendship and connection with those he deployed with, so he figured a club was something other veterans at Central would benefit from. “We also wanted to make positive impact on the community,” Dennis says.

Currently, the club is advised by Ruben Cardenas, Iraq Army veteran and director of the Veterans Center, and has five officers and five other revolving members. Dennis says there are usually about 10 people at every event or meeting the club holds.

There are also studies currently going on for MDMA-assisted psychotherapy, which can help heal the psychological and emotional damage caused by sexual assault, war, violent crime, and other traumas, according to the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS) website.

The studies are ongoing, but the clinical trials are only administrated a few times, compared to most medications for mental illnesses, which are typically taken daily for years, and sometimes forever.

Sidebar

CENTRAL PROPOSES LEGISLATION ON VETERANS' MENTAL HEALTH

By Christina Black

This past legislative session, student employees working in the Office of Legislative Affairs (OLA), with guidance from Central’s Assistant Director of Governmental Relations, Steve Dupont, wrote a bill that would make a very specific contribution to the work the Veterans Center does on the Central campus and other university campuses across the state.

OLA student legislative liaison Michael Brian Scott says he is spending countless hours in Olympia in support of this bill and as Central’s voice in the Capitol.

“In short, this bill gives schools money to hire one full-time Veterans-specific mental health counselor to be housed in the Veterans Resource Center, instead of the mental health office,” says Scott. This is only for the six major public 4-year universities, he notes. No CTC’s, private schools, branch schools, or branch campuses.

Scott explains that having such a specific position is to designate the counselor’s services directly towards veterans only. “The reason for having them in the VR center is to combat the stigma against seeing mental health counselors,” he notes. “ The goal is to make them just a friendly face, instead of a ‘therapist.’”

Therapists, Scott said, have no specific requirements or qualifications. Using a generic therapy approach to a specific a affliction like PTSD is next to useless. Unless the counselor has either extensive training or personal experience in a combat zone or trauma-inducing incidents, they simply cannot help veterans because they cannot relate.

However, making this vision of a counselor a reality relies on the legislative process and funding. Currently it is still underway with the com- mittee, and all status updates can be tracked on the Washington State Legislature page.

The actual bill, submitted to both House and Senate, reads

NEW SECTION. Sec. 1. A new section is added to chapter 28B.10 RCW to read as follows: Subject to the appropriation of funds for this specific, purpose, the state universities, regional universities, and the state college shall each employ at least one full-time mental health counselor licensed under chapter 18.225 RCW who has experience working with active members of the military or military veterans, to work with student, faculty, and staff veterans, as well as their spouses and dependents, through each institution’s veteran resource center.

Dupont says the bill has risks, too. “If the man-date in the bill is enacted without funding, it will be bad for Central because it will force a cut in other student services in order to fulfill the required mental health counselor that is dedicated to only Veterans.”

Anticipating that possibility, OLA also submitted SB 5592 that would allow decoupling of tuition from service and activity fees. If passed, the S&A committee would have the autonomy to adjust their income for fees based on demand. So if both 5592 and 1737/5525 are passed, the funds needed to pay a counselor annually would be established and veterans would have mental health counseling at their fingertips.

“Veteran students face unique challenges in higher education, and so another resource to them would be beneficial,” says Dupont.

Among the services currently offered at the Veterans Center are: academic counseling, career guidance, help for transitioning back to society, weekly study sessions, a Veterans Club, and information on grants and tuition waivers, like Police & Fire fighters, Veterans in Foreign Conflict Grant, and Survivors’ and Dependents’ Waivers.