Exotic Animal Conservation: How Accredited Zoos Protect Wildlife in Washington

Story by Kyle Wilkinson | Design & Illustration by Krista Kok

You may have seen episodes of Tiger King, a recently-released, limited series on Netflix. In this flamboyant cast of characters, a murder-for-hire plot and general destruction of limb and property, the namesake for the show is quite overlooked.

The importance and safety of the tigers and other large animals held in captivity fall out of the storyline as you follow the seven episodes from the edge of your couch cushions.

There are less than four thousand wild tigers worldwide, according to the World Wildlife Fund. Compare that to the more than five thousand tigers held in captivity in the United States alone. Less than 6% of those tigers reside in accredited zoological institutions.

Without an accreditation through national and international organizations, some of these institutions may be operating without the conservation of tigers — among other exotic animals — in mind.

Captivity Without Accreditation

At some zoological institutions, tiger cub petting and breeding is common practice, according to Lisa Wathne, a senior strategist for captive wildlife with the United States Humane Society. The issue with this is that tigers are being bred simply for generating more cubs to be used for social interaction with visitors.

Wathne points out that there is often a lack of oversight to maintain healthy genetic diversity when this happens. Once these tiger cubs grow too large for petting, they may be traded or sold to other institutions to continue the breeding process.

This is not beneficial to the conservation of big cats, according to Wathne. “A lot of people go to facilities and take part in the cub petting, believing that they are helping conservation and it just simply isn’t the case,” she says. “That’s really a ruse that these exhibitors put out there to people because they want to play on their sympathies.”

This type of interaction can be dangerous for animals and people, adds Wathne. Exotic animals require special care that some institutions may not be able to provide. Security measures also pose a concern for human safety in these types of situations.

Facilities that offer this type of interaction may only have a Class C Exhibitors license through the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) Animal and Plant Health Inspection.

Any institution can apply for this type of license and is subject to the standards for animal care through the Animal Welfare Act (AWA). Facilities that only acquire this type of license may be called ‘roadside zoos’ for their lack of partnership with other institutions and organizations.

These are the types of institutions that you may see on shows like Tiger King. Although these parks may be following federal and state regulations, they may not be providing the types of care required by an accreditation through an organization like the Association of Zoos and Aquariums (AZA).

Larger, interconnected zoos often have an accreditation with the AZA. Director of Animal Care at the Woodland Park Zoo in Seattle, Washington, Nancy Hawkes, explains that the accreditation is an involved process.

“AZA is not just interested in animal care — that is their primary focus,” Hawkes says. “They also look at the breadth of your organization, your education programs, your field conservation programs, your governance, your finances, the whole gamut.”

Hawkes points out that having this accreditation is beneficial in providing the best animal care possible. “The most important thing is that it ensures that you’re not only providing excellent care, but you are doing it for the right reasons,” Hawkes says.

Hawkes also points out that the accreditation allows the staff to grow off of the experiences they share with each other. There is cooperation and shared knowledge between institutions that everyone can learn from.

Brian Joseph, the state veterinarian for the Washington State Department of Agriculture, has spent a lot of his life working in zoos and aquariums. During his experiences at accredited institutions, Joseph has seen how animal welfare efforts have never been spared for the sake of the animals.

“Never ever in my entire life … has anyone ever said, ‘No, we’re not going to spend that money to provide the very best animal health care for that animal’,” Joseph says. “No matter what it was, no matter what it [costs], there have been no expenses ever spared for the animals.”

Zoos may acquire additional certifications and accreditations through groups like American Humane and the Alliance of Marine Mammal Parks. These are similar to an AZA accreditation, but with even more emphasis on the housing and care of certain animals and their living conditions.

While the USDA monitors the captivity of animals at a national level, it may not be as all-encompassing as other accreditations. “Really those other organizations that help us … push the envelope and raise the bar,” Hawkes says.

Zoos must also work in partnerships with entities like the United State Fish and Wildlife Service and National Marine Fisheries Service to acquire certain animals.

Other regulations may fall under the jurisdiction of the Endangered Species Act and Marine Mammal Protection Act.

Some states have their own sets of laws that govern zoos and wildlife parks in their jurisdiction. According to the website for Washington State Legislature, House Bill 1418 was passed in Washington State on July 22, 2007 and placed restrictions on the housing and acquisition of exotic animals.

Under this bill, Class C Exhibitors that acquired exotic animals prior to July 22, 2007 were allowed to keep their animals so long as they didn’t acquire more and didn’t breed their animals.

The bill also states that only institutions accredited by the AZA could acquire and breed exotic animals. This makes Washington one of the strongest states in terms of exotic animal laws.

Importance of Accreditation

According to their website, the AZA “helps its members and the animals in their care thrive by providing services advancing animal welfare, public engagement and the conservation of wildlife.”

This occurs through promoting public trust, increasing funding for zoological institutions and connecting professional animal care providers with animals in need.

Institutions like the Woodland Park Zoo are working to create conservation initiatives that promote the reintroduction of species. “That’s one of the huge parts of being accredited and having this network of support is being able to support conservation around the world,” Hawkes says. “And then be able to bring it back to our audience and talk about how your local zoo is making a difference in the world.”

But before reintroduction can occur, there must be some sort of education on why animals need to be protected and bred by zoos in the first place.

“I’m a pretty firm believer in reintroduction of species, but before you could reintroduce them, you have to correct whatever it was that pushed them to extinction. Whether it was too much use by people, whether it was changing habitat, whatever it was, you have to correct that,” Joseph says.

Accredited institutions often place an emphasis on education for animals and their native habitats. This can be beneficial when you see how a habitat is being impacted in your own backyard.

“The most important way to help all wildlife is to address the issues that are taking away wildlife habitat,” Wathne says. “Whether that’s in India with tigers or whether it’s in their own backyard, habitat loss is the greatest threat to all wildlife.”

One of the pieces of federal legislation right now that the Tiger King docu-series mentions briefly is the Big Cat Public Safety Act. This piece of legislation has been introduced to the United States House of Representatives and is awaiting further discussion.

This act would prohibit human-animal contact in regards to large exotic cats. It would also promote conservation of these species through limited breeding programs.

Hawkes also points out that this kind of advocacy is a large part of promoting conservation for accredited institutions.

“That’s a very gratifying part of the work that we do, really affecting change on a legislative level,” Hawkes says. “And I think that’s largely because of the resources that we have available to us.”

Your Impact

If you want to attend an unaccredited zoo or aquarium, be prepared for in-depth, interactive experiences with animals. You may also want to be aware of these types of institutions taking animals off-site and conducting their own breeding programs.

Accredited institutions will not generally offer these types of experiences. Wathne points out that this should be a red flag. “So if you see those kinds of offers, turn around and walk away. Don’t support it.”

You can also go to the AZA’s website and look up accredited institutions in your area.

Most of these institutions will have their accreditation and partnerships listed on their websites. This ensures to the visitor that the zoo or aquarium is held to the highest standards.

To promote animal safety, you can reach out to local representatives to make sure legislation like the Big Cat Public Safety Act passes into law.

Advocacy for conservation of wild animals can start at the local level, Joseph says, and work its way up to a national standing.

You can get involved today with an educational program and work with local zoos and aquariums. Many of the organizations that promote animal welfare and conservation will accept donations and volunteers.

Giving back may be one of the greatest things that you can do, according to Joseph. “We don’t all have the same number of years in our lives, but we have the same number of hours in a day,” Joseph says. “And we all have the opportunity to choose how we spend that time.”

So the next time you watch an episode of Tiger King or see a news story about the show, know that the roadside zoos in this story were not accredited by the AZA.

The show fails to place an accurate emphasis on the types of animal neglect that occured at these zoos.

Not all roadside zoos are necessarily bad and some may even provide great care for their animals. But if you want to truly learn about species conservation, consider supporting institutions that are accredited and engaged in your local communities.

Places to get more Information

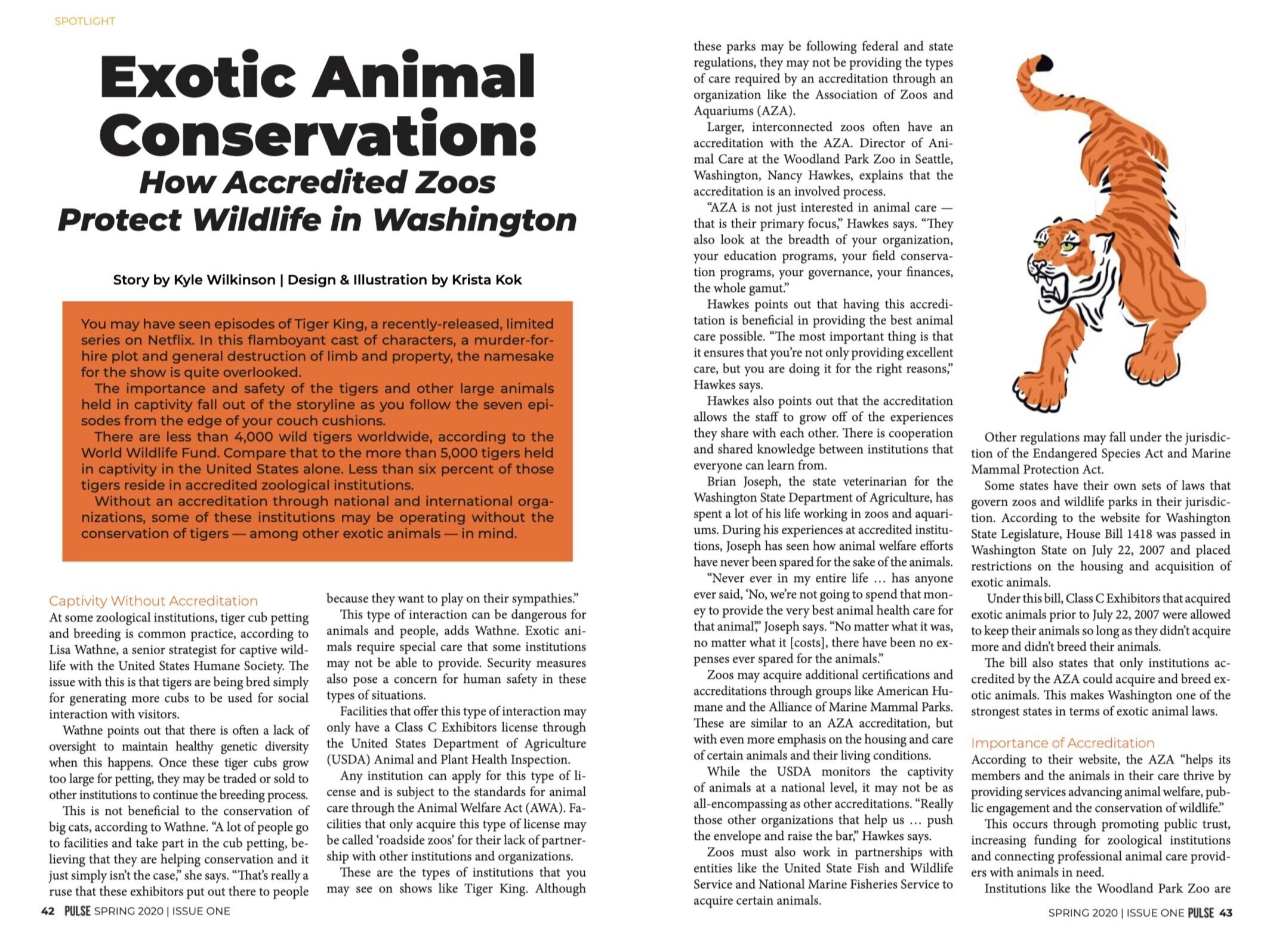

Infographic #1: AZA Accredited Zoos in Washington State

Woodland Park Zoo

Northwest Trek Wildlife Park

Seattle Aquarium

Point Defiance Zoo and Aquarium

Infographic #2: AZA By the Numbers

AZA-accredited zoo and aquarium professionals care for about 800 thousand animals.

More than 22.5 billion dollars was contributed by accredited zoos and aquariums in the United States in 2018

231 million dollars is spent every year to support conservation projects.

About 1,700 zoo and aquarium professionals have received quality education in the last five years.