Exploring Snoqualmie Tunnel

story by Amy Walker, photos Keaton Weyers, design by Amy Walker

This story won multiple awards including; a national second-place award for Multimedia Feature Story of the Year from Associated Collegiate Press at MediaFest25 and a regional Best Use of Multimedia award from the Society of Professional Journalists.

A tall, dark archway stands before you, framed by concrete and trees. Is it safe to go in? You can’t even see the exit. A breeze rushes down the mountain and presses against your back, ushering you in. You’ve just entered the Snoqualmie Tunnel, a dark and mysterious hike in the Cascade Mountains. The Snoqualmie Tunnel is a sliver of the massive 285-mile Palouse to Cascades State Park Trail. Like the name suggests, this trail stretches from Cedar Falls in the Cascade Mountains to the Columbia River to Vantage and ultimately ends at the Idaho border. Comparatively, the Snoqualmie Tunnel seems small. Yet, in person, it is massive.

The Snoqualmie Tunnel is the nation’s largest tunnel open to non-motorized traffic. Despite the looming mountains and the inky blackness, Snoqualmie Tunnel receives 200,000 visitors yearly, according to The Seattle Times. An impressive number given that the Tunnel is closed form November 1 to May 1. Hikers, joggers, cyclists, and equestrians all flock to the Tunnel, trusting their headlamps and flashlights to safely lead them to the end. But the Tunnel wasn’t always a place filled with pedestrians.

All Aboard the Milwaukee Road

Even today, crossing the Snoqualmie Pass connecting Eastern and Western Washington is a pain. Imagine the difficulty for travelers in the 1910s making the same journey. One railroad company, the Milwaukee Road, took on the herculean task of laying track through the Cascade Mountains. The route they charted was not easy to complete, however, as Milwaukee Road would need to tunnel 2.3 miles through the mountain range, 1,500 feet beneath the mountain peak.

To breach the face of nature’s giant, Milwaukee Road assembled manpower and firepower. Tim Schmidt, park manager of the Washington State Parks Lake Easton Area, recounted the construction of the Snoqualmie Tunnel during a reopening ceremony after the Tunnel was closed for two years for repairs. According to Schmidt, “about 2,500 men known as ‘tunnel stiffs’” were contracted by Milwaukee Road. These men were equipped with copious explosives to burrow through the Cascades. Specifically, the tunnel stiffs “removed 180,000 cubic yards of rock, detonating 340 tons of dynamite, blowing it up 100 rounds at a time,” Schmidt wrote. The Tunnel was completed in August 1914, and the first train journeyed through the Tunnel in January 1915.

Video of CWU students exploring the Snoqualmie tunnel.

While the tunnel was then completed, running a railroad through the Cascade Mountains was no easy feat. Washington’s vast mountain range was prone to blazing fires in the summer and destructive avalanches in the winter. Milwaukee Road’s solution to these environmental challenges was to electrify their pacific railroad in 1917. According to Washington State Parks, Milwaukee Road was the first transcontinental railroad to innovate their train lines in this way, and “soon became the nation’s model for railway electrification.”

As time passed, the railroad industry declined. Milwaukee Road dwindled into obsolescence, with their last train running its last route in 1980. In Milwaukee Road’s absence, Washington State saw opportunity. “Washington state began acquiring the right of way in 1981 and opened the first segment of recreational trail in 1984,” according to Washington State Parks.

What’s in a Name, Pilgrim?

It was one Chic Hollenbeck who lobbied Washington to acquire the land that used to make up the Milwaukee Road. Additionally, Hollenbeck founded the John Wayne Pioneer Wagons and Riders Association in the 1980s. According to their website, the John Wayne Pioneer Wagons and Riders Association holds an “annual, fully supported, ‘Cross State Ride’ that travels from west to east over 18 days on the ‘Palouse to Cascades Trail.’” This “Ride of a Lifetime” for wagon teams and horseback riders has an impact that is twofold. One, the ride adds legitimacy to the public's claim on the land and two, resists the interests of private landowners in controlling the land. To recognize Hollenbeck’s contributions to acquiring and protecting the trail, which houses the Snoqualmie Tunnel, was recognized as the John Wayne Pioneer Trail.

After decades of the John Wayne Pioneer Trail, in 2018, it was decided that the trail should be renamed. John Wayne Pioneer Trail stuck out like a sore thumb for multiple reasons. Updated policies from the Washington Parks and Recreation Commission required trails to be named after geographic locations, culturally significant events and places, geologic features, botanical, or biological references.

Randy Kline, the project lead for the commission, explained the other unsavory reason why the name was changed. Originally, “The John Wayne name was used to popularize the initial acquisition of the trail and support for the trail back in the 1980s,” Kline told the Seattle Times. “…Everybody knew John Wayne and he was associated with the American West.” However, the Western movie star’s reputation has soured over the years. His racist and homophobic remarks, like the ones made in a 1971 Playboy Interview, were incongruent with Washington’s image. Therefore, the John Wayne Pioneer Trail and Iron Horse State Park Trail were collapsed into one, more aptly named, Palouse to Cascades State Park Trail.

Mind Your Steps

This was not the first time I visited the Snoqualmie Tunnel. A coworker of mine, Dallin Millard, invited a group of us to the Snoqualmie Tunnel in October 2022. We went at night and only walked to the middle of the tunnel before turning back. For this adventure, Dallin and I planned to walk the complete length of the tunnel and all the way back, nearly 5 miles. I also recruited Keaton Weyers, one of PULSE’s photographers, who also brought his friend Justin Pearson. We decided to hike the tunnel on October 13, departing Ellensburg at 9am.

The Snoqualmie Tunnel is a hike like no other and requires special preparation. Being entirely underground, the Tunnel is significantly colder than the outside temperature. Furthermore, the Tunnel is like an air conditioning unit, with a chilly draft blowing from the entrance of the tunnel. I recommend you dress warm for the journey. You will get cold without layering. I opted for a shirt, sweatshirt, shorts, and long socks to preserve warmth without overheating.

As the Snoqualmie Tunnel is a retired train route, the pitch blackness hides the paved over train tracks. The concrete path bulges in the center, marked by potholes and puddles. Along both sides are wooden slats. Some are wobbly and some are missing, so walking on them is unreliable. For these reasons, it is important to wear good walking shoes and bring strong lights. I reached 17,000 steps the day of the hike. Unfortunately, my wimpy flashlight was basically useless. Luckily, Keaton and Justin brought stronger lights that both helped with visibility and with taking pictures.

Outside the Entrance

After an hour drive filled with music and conversation, we arrive at the Hyak trailhead off of I-90. This location, with ample parking and nice restrooms, is the closest spot one can get to the Tunnel by car. The trailhead isn’t terribly busy that sunny Sunday morning. While there is a fair amount of people on bikes and on foot, the trail is large enough that we are still alone for most of the journey.

A gravel road leads to the entrance of the Snoqualmie Tunnel, marked by signage mislabeling our location as the Iron Horse State Park, and another describing the history of the Tunnel. We walk down the path, the autumn-colored trees growing taller and taller, until I-90 is out of view. A cool breeze beckons us closer.

Around the bend stands the entrance to the Tunnel. Tall, dark, and ominous. The sign above the corridor is overgrown, illegible. At this end of the tunnel stand two giant, wooden doors, chained open, inviting us into the tunnel’s embrace. A smaller, metal gate brandished with the Washington State Parks logo is pulled to the side. This gate will block the public from the tunnel in the winter but is wide open for now. After a photo op at the Tunnel’s mouth, we head inside.

Inside the Tunnel

Light becomes fainter and fainter the further we walk into the Tunnel. The opposite end is indicated by a tiny white blip. 2.3 miles to go. We are enveloped by concrete wrapping around the walls and ceiling. A singular cable runs high against the wall on either side, with a sign warning us about the 15,000 volts that course through it. Along the ceiling are countless stalactites, formed by dripping water and calcium, some of which drips on our heads.

Occasionally, we must step aside for the cyclists to pass. If we do not hear their tires on the pavement, their bells are sure to warn us. The bike riders typically travel in groups, whether a family with LED tires, professional cyclists or people pulling their dogs in trailers. It is eerie to watch as these entities pass by, as only their lights are visible when they whisk by. For the split second that the cyclist is directly in front of you, a person is visible and they immediately disappear back into the darkness.

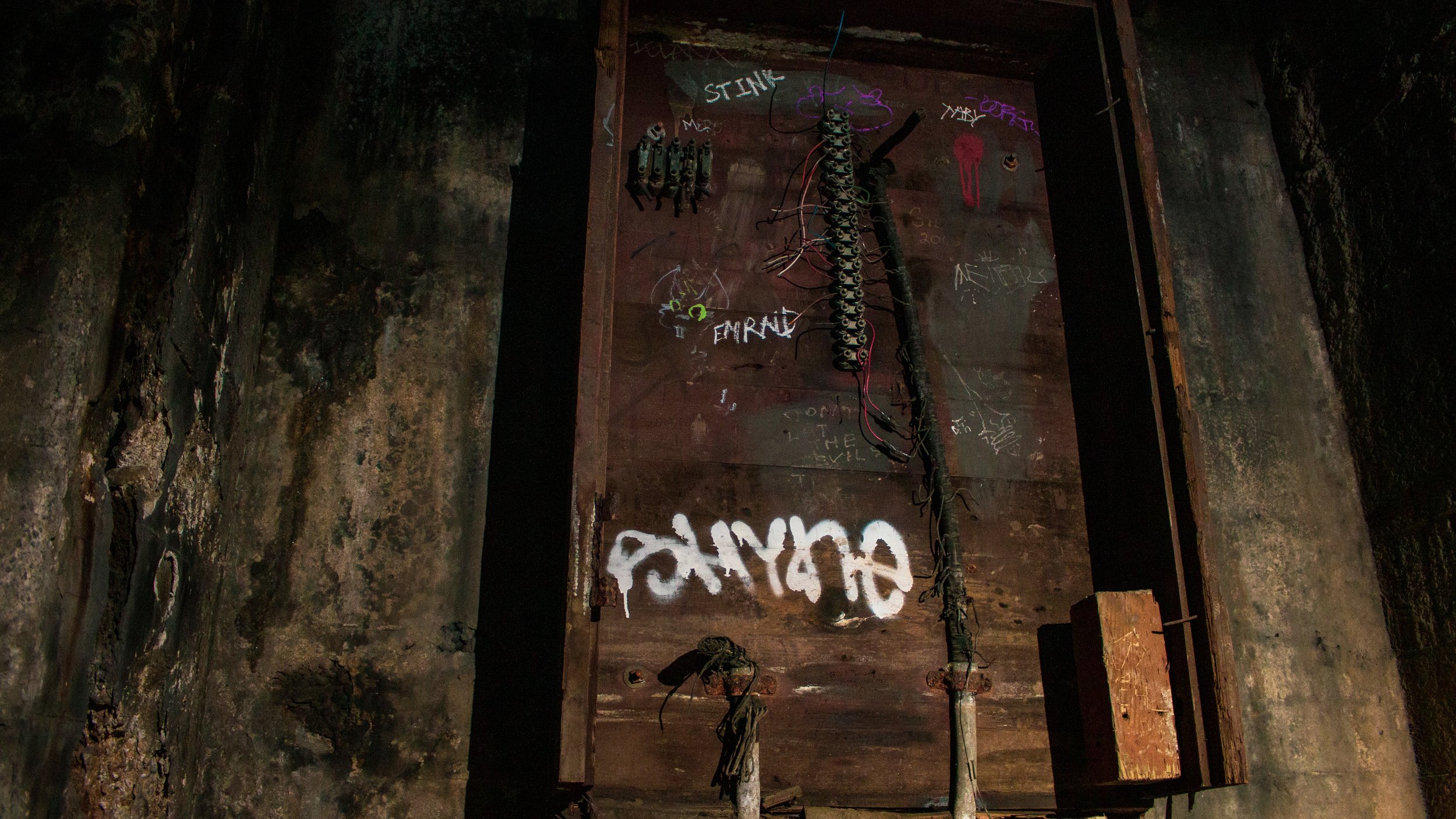

A repeating motif on the walls of the Snoqualmie Tunnel are graffiti and electric boxes. As with any concrete canvas, amateur artists have taken to decorating the Tunnel with drawings and profanity. There are plenty of bubble letters and signatures, as well as some more raunchy, and obscene messages peppering the walls. This includes ‘Tater Ball 420,’ ‘Bob is Bob backwards,’ and a mile marker for a past glow run, complemented by dripping smiley faces.

We discover that the graffiti glows under UV light and red light. The art can also be found on the electric boxes found in the Tunnel. Wooden boxes with rusty metal and exposed wires are rhythmically placed throughout. Each box is numbered with spray paint, as a useful marker in the all-consuming darkness. Typically, the electric boxes are tucked away into little alcoves. These alcoves were originally meant to protect the wiring from the train, but now act as a haven and hiding spot for weary travelers.

Tunnel Treasure

It’s likely that the last thing you would want to see while walking through the darkness is a zombie baby, and we spot two. Zombie babies are dismembered baby dolls that are frankensteined into unspeakable horrors. The creation of zombie babies is a time-honored Halloween tradition hosted by the art department at Central Washington University. Yes, this is art. Yes, this was made by one of our own. The first zombie baby is a doll crying black tears as a smaller doll head ruptures from its belly, painted like Joaquin Phoenix’s Joker. Unsettled but determined, we press forward. Further into the tunnel is a second zombie baby. This doll’s skin has crudely been painted green and its eyes pink. Its chest has ‘999’ written across it. An additional two arms have been attached to the doll’s sides, along with another, much larger appendage that I won’t discuss further. At the zombie baby’s feet is a burnt candle, which Justin relights.

Out of the corner of his eye, in the same alcove as the second zombie baby, Dallin spots a metal box sneakily shoved between two wooden beams. Upon further inspection, this is clearly not just a box, but a geocache. Geocaches are little nature-resistant trinket boxes with a tracker inside them. When someone finds a geocache, they sign and date the logbook and are invited to take an item and leave an item. Dallin signs the logbook as the rest of us search the contents of the box. While none of us take anything, Dalin leaves behind some tiny, multicolored, resin ducks that he had in his pocket. He returns the geocache to its rightful spot for the next person to find it. This doesn’t take long, as immediately a geocacher excitedly approaches us about the box.

This is Christian Giese, an avid geocache hunter from Munich, Germany. Lucky for us, Giese has a wealth of knowledge and expertise. He informs us that this geocache was hidden in 2004 and is named ‘Bloody Fingers, Dirty Diapers’ after a scary children’s story. This find is quickly logged in the Adventure Lab app, his personal favorite way to track the geocaches he has visited. Snoqualmie Tunnel is just one stop in Giese’s road trip from Los Angeles to Seattle, hitting as many geocaches as possible. We walk out of the Tunnel together, our eyes adjusting to the daylight.

The Other Side

The view is sublime. Giant power lines descend from the top of the mountain, disappearing into the vast landscape. Trees carpet the numerous peaks of the cascades. A firewatch tower crowns the mountain opposite of ours. The blue sky is endless. The afternoon sunshine warms us quickly. Such a profound contrast to the constrained darkness of the Snoqualmie Tunnel. We meditate on the view.

As we exit the Tunnel, Geise informs us of another geocache nearby. One of only two geocaches in the world placed to promote the” Planet of the Apes” movie. According to Geise, the geocache originally contained a torch from the film. After the prop was taken, the cache disappeared from its original spot for years, until it was eventually found further down the hillside. It is now back in its original location. This geocache is a bucket list item for Giese, so we follow him down the trail. After about a 10-minute walk, Giese discovers the geocache among a pile of white rocks. I grab an Animal Crossing button from the trinket box, and Dallin deposits a handful of ducks.

Before we return to the Tunnel’s abyss, we climb on top of it. On this end, the sign ‘Snoqualmie Tunnel’ is perfectly visible, and we want to take a picture sitting on top of it. First, Dallin scrambles to the top and back down to demonstrate that it is possible. The path simply requires some climbing. Keaton stays on the ground to take a picture while Dallin, Justin and I climb up the side of the tunnel.

Through the trees, up some rocks, over a stream, I am slowly guided up a safe path to get on top of the tunnel. Mind you, I am almost a foot smaller than the other guys, so every reach is a little bit longer for me. My foot slips. Adrenaline floods my body. I want this. I keep going. Finally, we crest the top of the tunnel. About 30 feet in the air, we sit on the edge of the sign. Somehow, all three of us up there are afraid of heights. After what feels like ages, Keaton snaps the photo, and we carefully backoff from the ledge. Cautiously, we retrace our steps back to the tunnel.

The Return Trip

We feel less fear, more reverence as we retread the Snoqualmie Tunnel. There are less surprises now, but we still stop for the occasional picture. With the cold draft blowing at our faces instead of our backs, we are constantly walking in the fog of our own breath. Occasionally, we turn off our lights and allow the shadows to overtake us. Our footfalls remain confident.

As we’re walking, Dallin informs me about the acoustic qualities of the Tunnel. Sound ricochets off the concrete walls and through the cylindrical space. An easy way to demonstrate this is by stomping on the wooden planks that line the floor. One well-placed stomp booms through the Tunnel. However, Dallin states, the peak acoustic echo is at the center of the Tunnel, which is also its darkest point. This gave us an idea. As we approach the halfway point, we all stop and dim our lights. Keaton, Justin, and I are silent. Dallin begins to sing, his tenor tone reverberating through the quiet. It’s a song he’s been practicing in his choir: “Der Müller und der Bach” by Franz Schubert. Slow and low, the solemn German lyrics haunt the Snoqualmie Tunnel. After that performance, it is hard for any of us to not burst into song and bask in the incredible acoustics of the Tunnel.

End of the Line

Slowly but surely, the light at the end of the tunnel blooms until we are fully lit by the sun. 5 miles later, tired, and hungry, we hurried back to our vehicle. Somehow, we managed to spend 5 hours with the Snoqualmie Tunnel.

After much research and preparation, we successfully conquered the Tunnel. This grand adventure took place only an hour out of Ellensburg, in a tunnel with many secrets to uncover. We investigated electrical boxes and graffiti; zombie babies and geocaches. We met kind people from outside the United States. We took in amazing views of the Cascades. And, most importantly, we gained an incredible reverence for this piece of Washington history. I anxiously await my next opportunity to hike the Snoqualmie Tunnel. On May 1, as the snow melts off the mountains, I will be right outside the gate.